You want strong parts. You also want cheap parts. The two don’t have to be at odds.

In this article, we’ll walk through the concept of “strength” and how to reduce cost in sheet metal parts while maintaining that strength by thinking about material and geometry choices.

Defining strength vs stiffness

First, terminology. Strength is not stiffness.

Strength

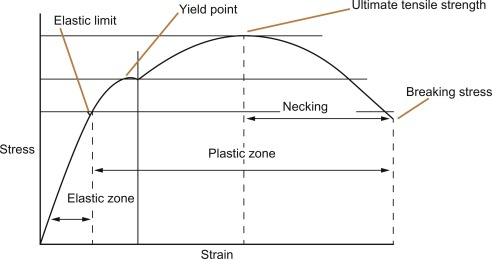

Strength is the ability for a part to withstand load without breaking. “Breaking” is defined by the engineer, and is pinned to a specific material property or a characteristic of the system. In general, we consider strength to be the ability of the part to take load without permanently deforming. In other words, how much force can I apply to the part without it permanently changing shape. We can do this by ensuring the stress seen by the part in any area is less than the “Yield Stress”, shown by the “Elastic Limit” in the diagram below.

Changing shape is a bad thing for many reasons. Quickly stating a few:

- You don’t know the new geometry of the part after permanent deformation. This is a problem because the new shape of the part could cause your assembly to not function correctly, or cause parts to dislocate in a way that removes assumptions you made while designing the part (For instance, your bolt heads may not develop a reliable frustum due to bolt holes deforming into elliptical holes versus the circular holes you initially assumed.)

- You don’t know your new strength characteristics (yield, ultimate tensile strength, etc.) after that permanent deformation

For mostly those two reasons, we treat yield stress as ground truth for strength and run analysis and FEA against that number. Once you get into the more demanding fields like Aerospace, you’ll start to see engineers design against ultimate strength in some cases.

Stiffness

So that’s strength – what’s stiffness? Clue: it’s not strength. Simply, it’s how much a part or material deflects under load, but it depends on how you ask the question. If you’re asking about the stiffness of a part, it’s a combination of the geometry of the part and the material.

Geometry of the part impacts how “stiff” the part is. See the image above – dimple forming enables greater section height which increases stiffness.

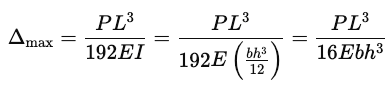

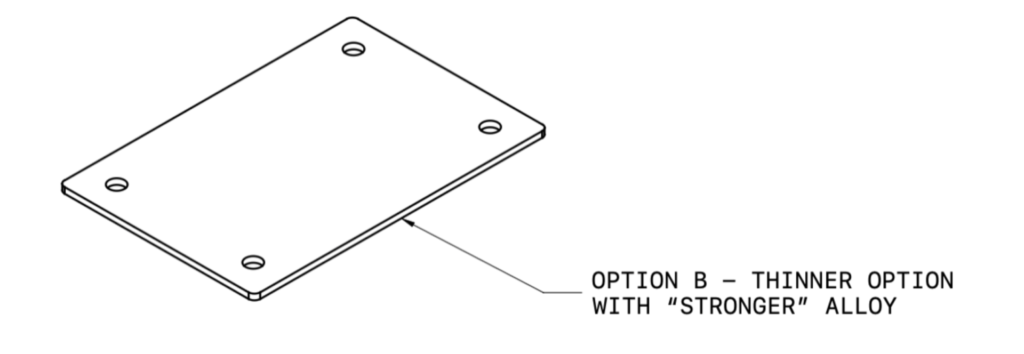

How? If you look at the cross section of the part where the dimple is, you can examine the deflection as a beam in bending. In this case, it’s fixed supported on both sides of the beam. We then find the equation for bending as a function of part height (h) below:

Where:

P is the load

L is the length of the beam (the sides of the part, in this case)

E is the elastic modulus of the material

I is the Second Moment of Area

Because we created a dimple, we formed the part in such a way that we created a larger h (depth) of the part. You can see in the math that because it can resist bending more, it reduces the deflection, and not by a little, but by a lot.

The equation above is a ratio of the pre change and post change deflection. If you doubled the height of the part, you’d see an 8x increase in strength. It is not intuitive and the math is useful for this reason. This is why dimples are so effective despite removing material.

So that’s the “stiffness” of a part. What about the stiffness of a material? In the above example, E (Elastic Modulus) is the “stiffness” of the material. It’s a property of every material. That’s why statements like: “Steel is 3 times stiffer than aluminum” make sense regardless of what the part geometry is.

This means you have two avenues to increase stiffness – either change the material, and/or the part geometry.

Enough about definitions – let’s get into an example of how to make a part cheaper.

Reducing cost while maintaining strength

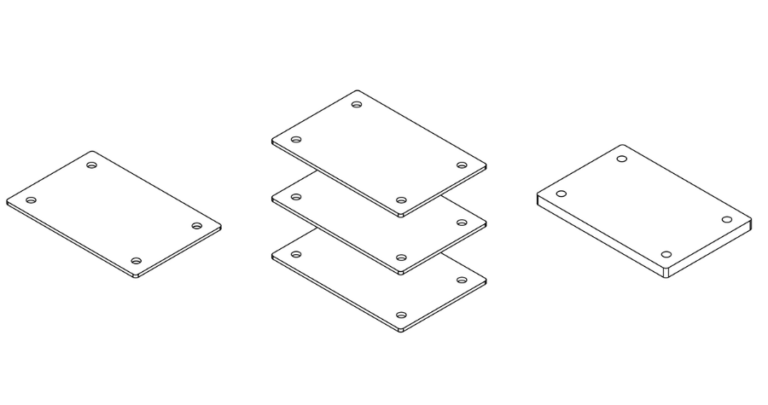

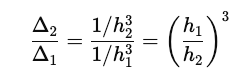

Let’s say you have a simple plate with four bolt holes for putting load into the part. These bolts put the plate into purely tensile axial loading. For those of us who had friends in high school, this is a way of saying that the part is only experiencing load in a way that would pull the holes away from each other.

Let’s say this geometry is determined and we don’t want to change it with one exception (thickness). This part will always look like this. Because we’re allowing ourselves to change the thickness, we can start to think about alternative configurations that could reduce cost and maintain or increase strength.

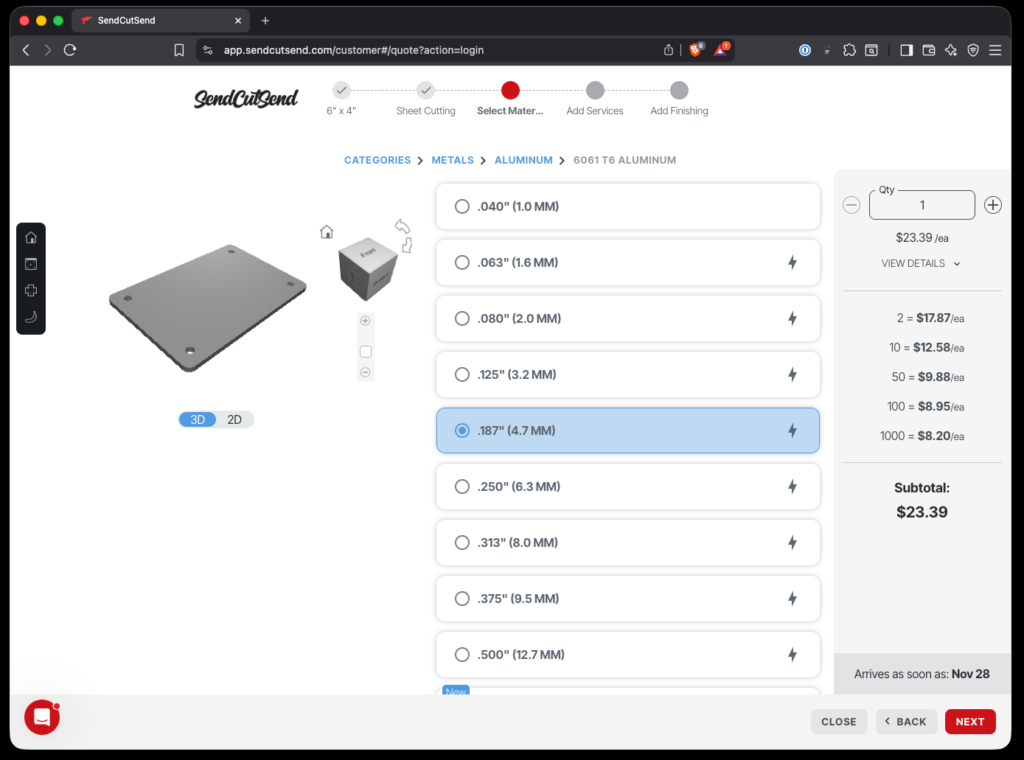

Example: let’s say you chose ⅜” 6061-T6 aluminum because you wanted some additional strength without a ton of additional cost. You have two options to reduce the cost and maintain strength.

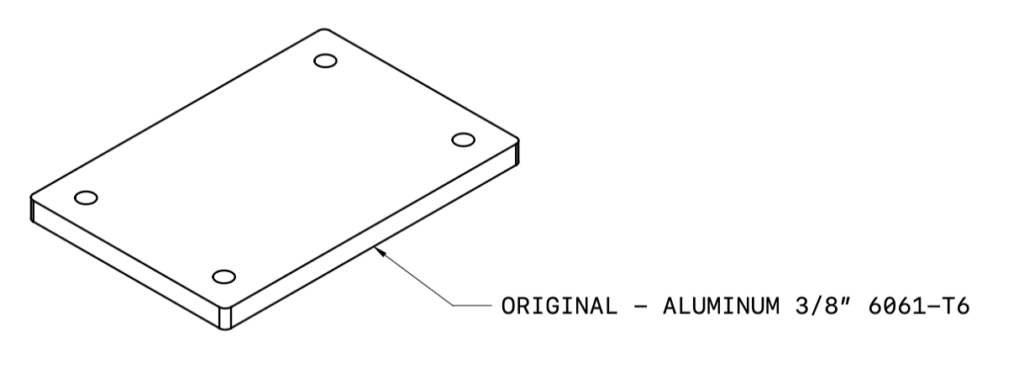

Option A: stack three thinner parts to equal the original thickness; in this case, that is stacking 3x ⅛” thick parts to equal the original ⅜” part. This reduced the cost by 20%. It really matters how the part is loaded, but if you know you don’t care about shear or bending stress then this is an easy win.

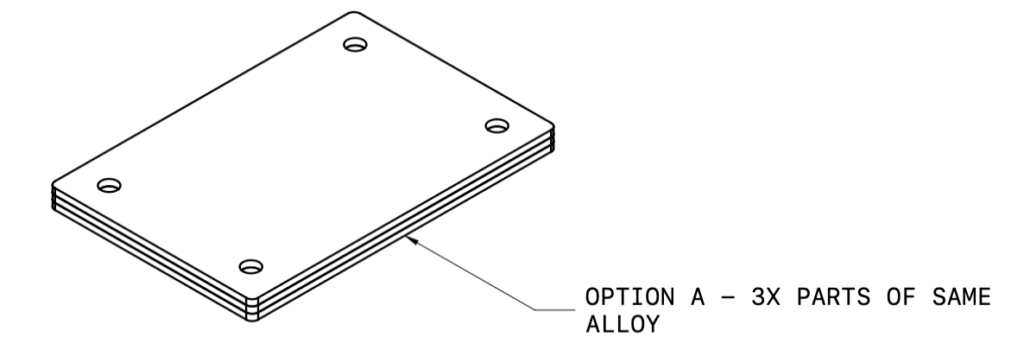

Option B: switch the material and thickness. SendCutSend’s material specs 6061-T6 show it has a 39 ksi yield stress. AR500 steel has roughly 187 ksi.

Because the cross sectional area scales linearly with the thickness of the material, this means we can divide the two and get what the minimum required thickness of our new material (AR500) would have to be. Get your calculator.

For a ⅜” sheet part, that means we can make an equivalently strong part at 0.081”.

The lowest AR500 thickness available at SendCutSend is 0.119” and comes in at 63% of the cost. We just reduced our weight, increased our strength and reduced our cost, all at the same time. Bingo. There are other factors to consider – AR500 is brittle and isn’t suitable for structural applications, etcetera, but you get the point.

Reducing costs in sheet metal parts

So there it is – a way to make parts cheaper without having to sacrifice strength. If you’re looking to reduce the cost of your parts, play around with some options before committing. It may be easier than you think to bring the cost down.

In the SendCutSend app you can quickly swap out materials and thicknesses so you can check these prices in real time with some basic strength assumptions.

———————————————————————————————————–

Emanuel Moshouris is an engineer based out of Seattle. He loves SendCutSend and writing about metal. You can find his engineering memes here: https://x.com/emm0sh